Ervaringen

Ervaringen

Read all about her experiences in Kisumu here.

I don’t know my neighbors. I know their first names – hardly at all, and they are only the neighbors who live in the same house. Left, right, opposite? No idea.

In Kenya this is not the case; in the small Christian communities everyone knows each other. Not only by name but also truly, as a human being. From neighbor to neighbor, from family member to acquaintance, people do see each other. People know how to find each other.

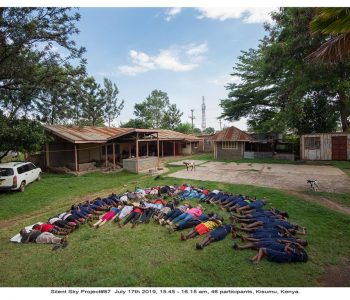

Last summer I spent five weeks in Kisumu, near Lake Victoria, with Mary Kizito and her family. Her family and her community. I know my uncle almost as well as she does her entire compound – when someone dies there is a community party.

Muzungu’s who are visiting, whites, are not necessarily excluded from this community. I was often told that I now had four mothers – Mary in the compound where I lived, Eunice in Pandipieri, Molly in the rest of Kenya and my biological mother in the Netherlands. In addition, three more women introduced me to others as their daughter or granddaughter.

All these wonderful women (except my ‘real’ mother) I met through the Kisumu Urban Apostolate Programme, also called Pandipieri, the organization I visited. This development project was started in 1978 by missionary Hans Burgman, who is now himself honored as a kind of saint with paintings and quotations on the walls. This NGO is still operational from a Catholic quasi-collectivist perspective in the slums of Kisumu. With an almost innumerable number of departments – I could only spend one day on each project in my five weeks – the community maintains itself. The programmes are mainly concerned with health care, education and various types of help for (street) children, including an HIV clinic, two schools, therapy, legal advice, rehabilitation, food aid, computer lessons and an art school.

I have visited all these projects and helped them as well as possible – most days consisted of mainly updating files, weighing babies and talking to bedridden patients – but I soon noticed that help from volunteers was welcome but fortunately often unnecessary. The idea of Hans Burgman (besides missionary also philosopher), that a community should help itself in the first place before others are involved, has been successful; a constant influx of Western money and Westerners themselves who leave after a month can never be as effective as getting a hundred people to get their own neighborhood up and running as well as possible.

This works best in societies where people already are dependent on one another. In a ‘meritocracy’ people forget that we are group animals – people function best in dynamic, overlapping and interdependent networks. I have a different nature of dealing with others than is the norm in Kenya. This clear cultural difference is especially noticeable in the easy way in which people deal with each other. You immediately give a hand when you see each other, even when you have known each other for weeks. If someone offers you something (food, drinks, the possibility to attend a funeral in the community) you agree, otherwise you are rude. You can always ask a white person for money; they have enough.

Difficult for an individualistic individual to get used to. In the Netherlands it is often more polite to refuse, not ask, not to initiate physical contact. When I told them that I didn’t have my suitcase the first few days, I heard ‘why didn’t you say that? You could have borrowed my clothes/sunburning/toothbrush’, even though I felt that I didn’t know anyone well enough to demand even more favors; I could stay here for less than six euros a day anyway?

This strange way of doing things unfortunately remained for me partly a play. The disadvantage of each group is the group pressure that comes with it. In Kenya, as a non-Catholic (especially if you are in an Apostolate Programme), homosexual and/or unmarried woman, you quickly fall out of the boat. I had to lie all the time to find my place – not only to rescue my own skin, but also because I didn’t want to saddle my temporary community with something like that. On the one hand, there is little reason to be confrontational about identity issues (lifelong Catholics don’t change their opinion quickly in my experience); on the other hand, I wouldn’t recommend anyone to hide behind an identity that isn’t their own for weeks.

Of course I have nothing to complain about. I live in the Netherlands, probably the most tolerant country in the world. I have nothing to endure, compared to quote-unquote people like me who live in Kenya. Or Saudi Arabia. Or Russia, or the Dominican Republic, or Iran, or India, and so on.

That aside.

I also have had, of course, positive experiences. Working with the children was great. I spent several free afternoons and Saturdays in both schools: the nursery school for small children from the neighbourhood whose parents could not afford the normal primary school and the ‘Non-Formal Education’ for street children who live at Pandipieri. Many of these children have run away from home due to abuse or abuse and have therefore not been to school for years. They are allowed to voluntarily live for three months at the compound of Pandipieri where they receive education and their supervisors do their stinking best to find a guardian for them. After three months they have to leave – Pandi’s facilities are very limited and there are always more children in need.

One boy, Simon, thirteen years old, who came to me right away, had not been to school for four years when he was approached on the street by Philip, the Pandi employee who travels through Kisumu and is looking for children forgotten by society. Nevertheless he was very curious; do dinosaurs really exist? What is that book about? When was the Korean War? Every sentence started with ‘Let me ask you something…’ and he always wanted to hear more.

All in all, taking the difficult and the beautiful into account, I am very happy that I got this chance. I hope that all Dutch people can experience a different culture in this way, but especially that my Kenyan friends can also come here. That they experience it all true is what I have told. Yes, my hair is automatically that steep. No, the AOW scheme is not a socialist fantasy. Yes, our king really is the boy who visited you in 2007.

We shouldn’t have to experience Africa personally to realize that other cultures are worth as much as our Judeo-Christian. Yet many people would do well to experience something different from the average Dutch for a while. Although I wouldn’t do the horror of Baudet to Africa.

Clara Eggenhuizen, V6C, 2018